Every moment of happiness that the documentary Amy portrayed was foreshadowed by the knowledge of her sad and premature death. We watched as a young women who loves singing and writing poetry was transformed into a 21st icon, a global superstar and a figure of hate. Learning of Amy Winehouse’s alcoholism, bulimia and drug addiction I felt ashamed for having judged her in the past – I remember reading about the gigs she cancelled and I remember thinking that she had let her fans down and been selfish. I had no idea of the context. As I watched I also felt complicit in the diabolical system that contributed so heavily to her death. And as the film shows it all began with her ability to sing.

A short clip of Winehouse as a teenager singing Happy Birthday to a friend begins the film and immediately demonstrates her talent. She states on numerous occasions how much she loved singing. Of course, her love of music was what made her and broke her because a voice like Winehouse’s is the perfect voice for commodification. Without ever stating it the film shows what happens to a successful artist in a consumer capitalist society. It began by assigning Winehouse’s voice a price tag. Be it as recorded songs on a CD or as a ticketed performance these were all ways people could make money from her voice. As she became more successful so her voice became worth even more – her album Back To Black sold millions of copies worldwide. Her increased popularity tied in perfectly with the underlying logic of capitalism, namely growth – keep exploiting a resource for profit until it’s depleted.

So Winehouse’s art was continually exploited. The film shows bleak clips of various people close to her using her celebrity status and wealth for their benefit. Her father, ex-husband, managers and production companies (Universal Music Group included) are all shown pushing her to perform more and produce more music. Her rise in monetary value coincided with her increased addiction to drugs and alcohol yet so many of the people around her did not stop to ask too many questions – why would they when they were getting so rich? Meanwhile, the press and her fans treated her as an idol. They garnered her with almost mythic status and placed her on a pedestal that she never deserved to be on. Of course, the paparazzi were all to happy to wrench her down from this plinth when her addictions and suffering meant she could no longer perform as a commodified celebrity is expected to. One moment that sticks out from the film is when she’s onstage at Belgrade and as she stumbles and falls the band look on and laugh. Meanwhile, the audience cheer her and then, when she doesn’t sing, boos her. “Sing or give me my money back” chants some of the crowd.

Commodity, idol, hate-figure, voice, character in a documentary – it seems one of the things Amy Winehouse was rarely treated as was a human.

I contributed to this process. I bought her album Back To Black, thereby adding another figure to her record sales, further assuring her success. I did not look to the woman behind the music – a woman suffering from depression, bulimia, substance abuse and abusive relationships – I heard her only as a beautiful voice. This process continues today. Her death will have significantly boosted her sales figures and the film Amy will make Universal Music Group an awful lot of money. As the credits rolled I saw that even Winehouse’s teenage rendition of Happy Birthday caught on a video camera by her friend is owned by a record label – even that brief song has been commodified. Under capitalism nothing escapes the profit motive and all is governed by a certain form of addiction – the addiction to money.

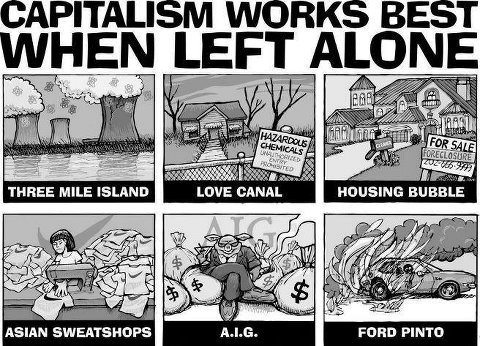

Amy the film is not the final say – it’s a carefully edited version of events that tries to tell one particular story. It paints her ex-husband and father as simple villains and never really tries to understand their behaviour. It also turns Amy Winehouse’s life into a slick narrative with a clear beginning, middle and end – her life is contextualised by her music and her tragic death. Of course, the one person who had no say in this process was Amy Winehouse – once again she is robbed of a voice and presented as a certain sort of person – the sort of person whose ‘story’ will attract lots of people to cinemas. This is the numbers game of consumer capitalism – a game that can cause climate change, facilitate resource wars, initiate global recessions and, most certainly, relentlessly capitalise on a vulnerable but talented young woman far beyond her death.

This system will change but for now I’ll leave you with one of Amy Winehouse’s brilliant songs: