Following the election many are saying it is time Labour went back to the drawing board and engaged in some serious soul-searching. Two such pundits include Pat McFadden, shadow Europe minister, and Owen Jones, Guardian columnist. Below I analyse their views and argue that both do not go nearly far enough because they don’t address the underlying issue – an issue much bigger than a Labour party rebrand and petty party politics. In truth, it is an issue as big as capitalism itself.

McFadden was quoted in a Guardian article saying: “…if there was one thing Ed Miliband was clear about, he was turning the page on New Labour even more emphatically than Gordon Brown was, and we see the results even more emphatically last night. We don’t just need a new person at the top of the Labour party, we need a new argument, too. We will always be the people of the lower paid, but we need to be more than that and be the party of the aspirational family that wants to do well. We need to speak about wealth creation and not just wealth distribution.”

In his article Jones recounts the Conservatives’ masterful victory over their left-wing rivals: their successful scapegoating of the Labour Party for the 2008 recession, their forcing of Labour to turn their backs on immigrants and the right-wing media’s stirring of Scottish nationalism to ensure a mass shift to the SNP and their stirring/scaring of English nationalism to ensure more blue votes. The Tories severely weakened their opponent and are enjoying a majority for it. He concludes with his aspirations for a new Labour politics as so: “There will be a big debate now over the future of the Labour party, and what the left does next. This country desperately needs a politics of hope that answers people’s everyday problems on living standards, job security, housing, public services and the future of their children. That is needed more than ever, no matter what happens with the Labour leadership. What is needed is a movement rooted in the lives of working-class people and their communities. The future of millions of people depends on it.”

*

I do not think either of these views are good enough. McFadden argues that Miliband’s leftwards shift from New Labour policies was a mistake. Now, Margaret Thatcher herself said that her greatest legacy was Tony Blair – he adopted right-wing neoliberal policies that she had initiated. He turned his back on the working classes and encouraged a capitalist rhetoric of ‘get rich and get middle class’. But the constant surge of boom and bust in capitalist economics, increasing levels of inequality and the squeezing of the middle prove that when push comes to shove the middle classes will be ignored by the establishment. We know trickle down economics are a sham as we witness the elite 1% drain wealth from wider society (e.g. in the public bailout of the banks and in the privatisation of the public sector). Yet McFadden still suggests that a traditionally working class party try to out compete a party that represents the wealthy establishment on the grounds of ‘wealth creation’ – good luck to them.

Meanwhile, Jones calls for a politics of hope rooted in working-class communities. Yet his book Chavs: The Demonisation of the Working Classes demonstrates how severely the working-class has been undermined since the class wars of Thatcher – working class industries obliterated, trade unions weakened and workers’ rights eroded. The working-class reality today is 0 hour contracts, abysmal working conditions (e.g. as in call centres), food banks and increasing poverty. Thatcher said there was no such thing as society and it seems her prophecy has proved self-fulfilling. So, whilst Jones’ critique is insightful his proposal is lacking. We need much more than a vague politics of hope: we need a pragmatic plan of action informed by an inspirational vision of what our society could be. We need a plan and vision that transcends petty party politics and, above all, transcends capitalism.

*

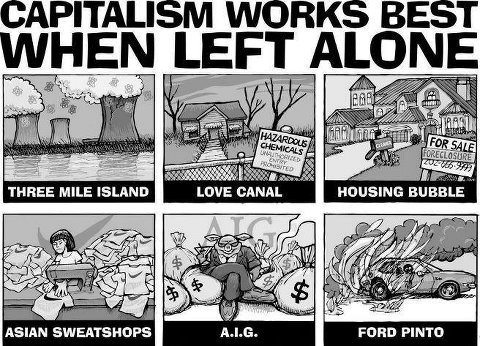

The recession of 2008 was not the fault of Labour it was the inevitable result of a deregulated and globalised banking sector that was ‘too big to fail’ and working under the ‘maximise profit’ mantra of capitalism. This trend of deregulation dates back to Thatcher and was not stalled by Blair, Brown, or Cameron. The rise (and rise) of the banking sector was a cross party achievement. Of course, the 2008 recession was just one of many – recessions are endemic to capitalist economics as bubbles are continually over-speculated upon and then burst. So Gordon Brown promising a departure from boom and bust economics during New Labour’s years, the Tories blaming Labour for the 2008 recession and George Osborne taking credit for the apparent economic recovery, are all just examples of a severely limited understanding of economics.

Neither McFadden nor Jones attempt to analyse the system of capitalism itself ensuring their proposals are either ill-informed or too flimsy. Booms and busts occur in capitalist economies because they have to – we are locked into a system that demands continual growth so we innovate new products and industries to ensure more money can circulate, and as the innovations increase so people speculate on them to make a profit. When one well of profit dries up the infrastructure built around it collapses and the speculators start mining elsewhere. Profit maximisation is even inscribed in law as companies are obligated to maximise shareholder return on investment. We are literally locked into a system that demands us to make money before anything else. Unfortunately, Jessie J got it very wrong, it is about the money.