The sixth mass extinction has begun and this time the cause is not a giant asteroid colliding with the earth, it’s us, human beings. And as the animals, plants and sea life die at a rate 200 times greater than if humans did not roam the earth my smart phone buzzes to reveal I have a new Tinder match. Shall I message them or ‘keep playing’? I’ll keep playing.

Tinder first, then the mass extinction. Tinder is a dating app that lets you view a few photos of people as well as a short paragraph about them. If you like them you swipe right, if not, left. Then onto the next one. If you both like each other you match and then you can start messaging one another, so at least you won’t have to send speculative messages to people who aren’t interested. So, it’s a simple way to connect with possible hook-ups, dates and lovers utilising the latest smart phone technology. But I think it’s more than that.

I think it’s an app that could only have come about in a time of great loneliness and isolation. As our means of communication increase so our means for community diminish. Local pubs, shops, clubs and libraries, to name but a few community centres where you might bump into a potential mate, are vanishing as rampant consumer capitalism punches its marks all over our cities, towns and villages. And these consumerism hubs aren’t about spending time they are about spending money – as many paying customers in the shortest time possible please. Public space is being privatised to facilitate shopping, making it increasingly hard to ‘bump into’ a potential lover (instead there’s Happn, another dating app that uses GPS technology to introduce you to people you’ve crossed paths with). In essence, these apps are trying to fill the gaps that are left behind when community vanishes. So I comb my hair in the best possible direction, turn to the light and angle my camera phone to take as flattering a picture as possible, hoping someone’s going to swipe right.

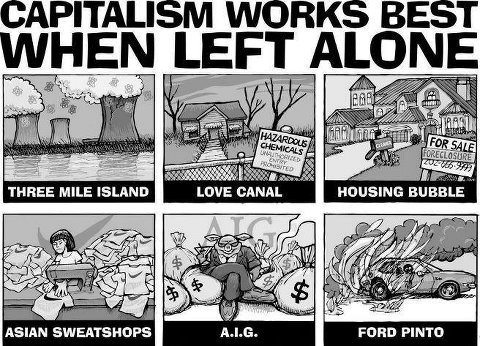

And now for the mass extinction. Well, it’s linked to that relentless consumer, capitalist society that I mentioned earlier. Not only does it depend on people being lonely and dissatisfied so they buy more things to compensate, it also depends on an endless supply of natural resources to make the things from. Resources including clean water, clean air, rare minerals, fossil fuels etc. So as we chop down forests, eviscerate mountains and pollute our oceans and atmosphere it’s no surprise that things keep dying – animals, plants, fish, etc. Consumer capitalism doesn’t just threaten human communities it undermines biological communities as well, whole ecosystems are razed to the ground for profit. Where exactly will the Amur Leopard hang out so she can meet a potential mate if her home is being destroyed? There’s no Tinder for endangered species.

So, it turns out that Tinder and the sixth mass extinction do have something in common: they both reflect a loss of community. Whilst the former is an attempt to deal with this loss, the latter is a very tragic consequence of living in the Anthropocene – a time that began when human activities started having a big global impact on the earth’s ecosystems (probably when industrialisation kicked off). Of course, there’s much to criticise Tinder for – namely, for reducing love to a smart phone app. But I think beneath the simple swipe of a finger there is a deep yearning to connect beyond the brands, logos and selfies and meet someone or someones we can truly come to know, someone with whom we can build community. We yearn to connect with others and I believe, so long as this yearning persists, there will always be a desire for more than this, more than the world of consumer capitalism. A world in which humans flourish as part of larger, thriving biodiverse ecosystems. So I swipe right hoping to find someone I can share the highs and lows of the sixth mass extinction with…